| OECD Trade and Environment Working Paper No. 2006-02, Hight & Ferrier |

|

| Thursday, July 16, 2009 | |

Joint Working Party on Trade and Environment: The Impact Of Monitoring Equipment On Air Quality Management Capacity In Developing Countries: OECD Trade and Environment Working Paper No. 2006-02: Reflecting the desire for cleaner air, many developing countries have enacted clean air laws similar to those of developed nations, although to date most of these laws have been poorly enforced. A key starting point to better enforcement is obtaining comprehensive and reliable air-quality monitoring data. This report explores the impacts of air quality monitoring programmes implemented over the last decade in five developing countries: Morocco, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, and India. These case studies also examine the role of procurement of specialised equipment, usually imported, associated with the various air quality monitoring programmes. The Impact Of Monitoring Equipment On Air Quality Management Capacity In Developing Countries Air quality data: the first step toward cleaner skies in the developing world Air quality in many developing countries, particularly urban centres, has become severely polluted over the last several decades as a consequence of industrial development, economic growth and large-scale migrations by rural residents to cities. Air pollution degrades the health and quality of life for people. Air pollution also exacts direct costs on national economies in the forms of reduced productivity and greater demand for medical services. In addition, there are indirect costs that are rarely accounted for such as the decreased value of the natural resource ‘asset’ of clean air in a nation, decreased tourism and even reduced foreign investment as a result of polluted air or other environmental and health impacts of polluted air. Citizens in the United States, Japan and much of Europe enjoy relatively clean air thanks to enforcement of air quality laws and market-based incentives for emitters to reduce their output of sulphur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxide (NOx), particulate matter (PM) and other pollutants. But efforts to reduce pollution lag significantly in most developing countries largely because the costs of obtaining cleaner air — through such measures as replacing and upgrading vehicles and installing air pollution control devices on industrial facilities and power plants — represent a large investment relative to national economic output. Nonetheless, there is a strong interest in improving air quality among citizens and leaders of developing countries with heavily polluted airsheds. Reflecting the desire for cleaner air, many developing countries have enacted clean-air laws similar to those of developed nations, although to date most of these laws have been poorly enforced. Regional initiatives such as the Air Pollution in the Megacities of Asia (APMA) and Clean Air Initiative for Asian Cities are aiding national governments and developing transnational strategies for cleaner air; and multilateral institutions such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank are funding air-quality management programs. The challenges to improving air quality in developing countries range from a lack of government commitment to even weak policies and standards to lack of accurate air-quality data, according to APMA’s Strategic Framework for Air Quality Management in Asia (2004). All these obstacles must be overcome to improve air quality in developing countries, but a key starting point is obtaining comprehensive and In the Philippines, for example, acquiring accurate and reliable data on the sources and levels of air pollution is viewed as a crucial first step in implementing national clean-air policies. While the government has the legal authority to regulate emissions through fees or taxes on major emitters, according to Air Pollution Control Policy Options (2003), a report by Resources for the Future, it must first develop the capacity to compile specific emissions data and validate data from emitters. The agency must also determine the “precise extent and distribution of stationary source and other emissions in Metro Manila,” according to the report.

Five case studies: NGOs, Governments and businesses collaborate to build air quality monitoring capacity A range of air quality monitoring projects has been implemented over the last decade in developing In all the case studies except for the Indian fuel testing project, imported air-quality monitoring equipment was crucial to the programmes’ successes. Such equipment is not manufactured to any significant degree in developing countries at this point. (In the Indian case, advanced imported equipment for fuel testing would have increased the speed and efficiency of testing, but project funding limits forced the investigators to use older, indigenously manufactured equipment.)

|

Submitted by Singapore

AIM

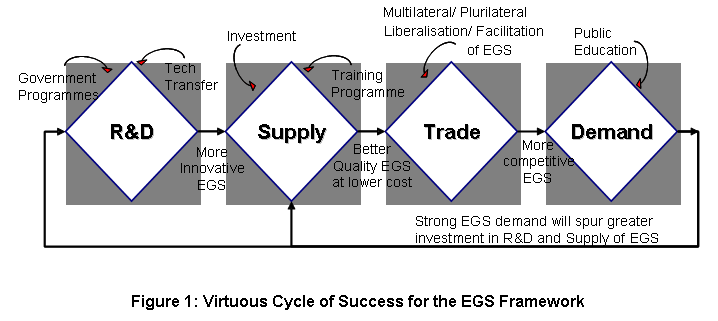

This paper seeks CTI's endorsement on a work programme framework for environmental goods and services (EGS) in APEC.

...

Submitted by Singapore

AIM

This paper seeks CTI's endorsement on a work programme framework for environmental goods and services (EGS) in APEC.

...